It’s your last chance to back Dice Exploder season 3 on Kickstarter!

The campaign ends Friday, October 6th! Here’s the link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/sdunnewold/dice-exploder-a-tabletop-rpg-design-podcast

This week I’m joined by Tasha Robinson, film editor at Polygon, Games on Demand aficionado, Golden Cobra honorable mentionee, and author of this excellent piece about today’s game and mechanic: Fall of Magic and the five and a half foot long handprinted scroll at its heart.

There’s a lot to say about such a unique physical object, and also a lot to cover about maps in RPGs at large. We get into all of it. Consider this the third part of the travel series this season opened with.

Pack your bags. It’s a heck of a journey.

Further reading:

Fall of Magic by Ross Cowman

Tasha’s article about Fall of Magic and City of Winter

Tasha’s article about larps about AI

Tasha’s archive on Polygon

Tasha’s Golden Cobra honorably mentioned larp The Regency Committee on Decorum and Punchbowl Poop Prevention

Rusalka by Nick Wedig

Drawing Out the Demon by Liz Stong

Doskvol Street Maps by Tim Denee

Blades in ‘68 on Twitter

Beak Feather and Bone, another mapmaking game from Possible Worlds Games

Dread by Epidiah Ravachol

Socials:

Sam on Bluesky, Twitter, dice.camp, and itch.

Our logo was designed by sporgory, and our theme song is Sunset Bridge by Purely Grey via Breaking Copyright.

Join the Dice Exploder Discord to talk about the show!

Transcript:

Sam: Hello, and welcome to another episode of Dice Exploder. Each week we take a tabletop RPG mechanic and follow it to the ends of the earth. My name is Sam Dunnewold, and if you're listening to this before Friday, October 6th, there is still time to back the Kickstarter for Season 3 of this very show. Alex Roberts of Star Crossed Mikey Hamm of Slugblaster, Strega Wolf of Lichoma John freaking Harper of too many games I've covered on this show, plus a hell of a lot more. Go now, while there's still time.

But today, on this episode, my co host is Tasha Robinson. Here she is, introducing herself.

Tasha: I'm Tasha Robinson. I'm the film editor at Polygon. com, which is fairly known for its game coverage. I'm a podcaster with the Next Picture Show podcast which contrasts a new film with an old one that speaks to it in some ways. And little known, apart from my occasional podcast appearances, I'm a big RPG I design games. I play a lot of indie games and I love having conversations like the one we're about to have.

Sam: More specifically, Tasha's a Golden Cobra honoree for her game The Regency Committee on Decorum and Punchbowl Poop Prevention. And, hell, I'm just gonna say it, Tasha is straight up my favorite film critic, and has been since, like, 2015. You should check out her work.

But this isn't some stinkin podcast about photographs rapidly projected on a wall to create the illusion of motion. In this house, we create the illusion of motion with our imaginations. And I asked Tasha to come on the show because of a piece she wrote for Polygon about Fall of Magic.

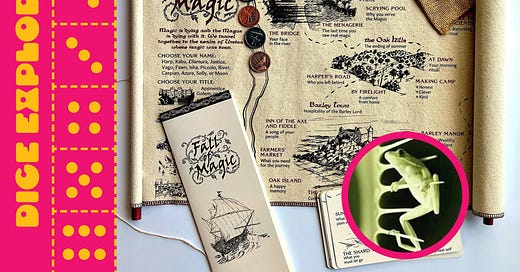

Fall of Magic by Ross Cowman is a fantasy game in which magic is leaving the world and you're all accompanying the Magus on a journey to the birthplace of magic to see if anything can be done about all that. It's a very rules light game and the primary mechanic is a five and a half foot long hand printed scroll.

Tasha's piece about it in part documents her own Fall of Magic campaign. While most people play Fall of Magic over the course of a few hours, maybe like 3-6 sessions in total, Tasha wrote about playing this game for 3 and a half years. Over 70 sessions.

I got to play it myself this summer in a single 12 hour sitting, which was magical. And, you know, we had to skip a few locations, but we finished content and complete. But I could not let it go. 12 hours is a lot shorter than 3 and a half years! What was going on? How? I had to know. I had to ask her about it.

Plus, like, Fall of Magic is amazing. And I was opening this season of the podcast with a two part episode on RPGs and travel, and not talking about Fall of Magic and its beautiful map felt borderline irresponsible.

So, I reached out, and Tasha and I had this conversation, as expansive as the scroll itself, about Fall of Magic, its spiritual sequel, City of Winter, maps of all kinds in RPGs, and how you can get so much out of a game that feels so simple on the surface.

So without further ado, here is Tasha Robinson with Fall of Magic's 5 and a half foot long handprinted scroll.

Sam: tasha Robinson, thanks so much for being here.

Tasha: I am very excited to be here.

Sam: Me too. I, hope we contain the length of this episode. What

Tasha: like we're about to go on a journey together and we're not sure how long that journey is going to be. If only we had some way of keeping track of the travels through this conversation somehow.

Sam: like a, like a five and a half foot long hand printed scroll.

Tasha: That's a good idea. I don't know why nobody has thought of that before for tracking conversations.

Sam: Yeah, yeah got a real winning idea there for the next tech billionaire looking for one. Tell us a little bit about Fall of Magic, Tasha. I know I've invited you here to talk about it, but I would love to just hear you describe this game and your experience with it.

Tasha: So, Fall of Magic, designed by Ross Cowman, is a kind of a narrative, collective storytelling prompt game. And it's based around this map, which is a beautiful physical artifact. There is a digital version of the game that you can buy that's way, way cheaper. You know, you just get some... Some online PDFs to download, but if you want the real deal, it runs last I checked about 125 because it is a handmade canvas scroll.

I interviewed Cowman about the design on this game when he was doing the semi sequel, semi spinoff,

City of Winter, which I think we'll also talk about, which is another map game. But effectively what he said was, a part of the fantasy genre, like beloved to a very small percentage of fantasy fans, and is the big expansive world map. And he wanted a game that was based around that

concept of a world map.

So when you sit down to play Fall of Magic, your character creation consists entirely of picking a name from a list of names and picking a... a profession isn't necessarily the right word, but a signifier,

Sam: Title, maybe?

Tasha: Yeah, you could call it whatever you want, because you can read it however you

want. Like, some of them are Midwife or Golem. Some of them are, like, Fox or Raven. When we sat down to create our game, I created somebody who was a Raven, but then I didn't define that as a bird. I defined it as a specific magical creature that had been created with a, an amalgamation of human magic. So you can define your terms however you want. All you have is a name and a one word descriptor.

And then you set out on a journey. And the theme of the journey is that magic is dying and the Magus is taking you to Umbra, the place where magic was born, to see what you can do about it. And as you move from location to location on the map, each location has a series of story prompts, and they're very simple. They'll say things like "in the heart of the machine," or "standing by the river," or "two roads in a woods."

And on each location, you have these very nicely minted little two sided coins. Everybody has selected one to represent your character. And as you get to a new location, you move those coins to a prompt and start a scene.

And it can be as simple as just describing your character in that location, having that experience, or it can be a big interactive thing.

And in that way, you move across the map, you tell a story together. Umbra is at one end of the map. It's a two sided map. You have the option of taking a bunch of different routes to get where you're going, but eventually, in theory at least, you get to Umbra and find out something about the fall of magic.

I have talked to someone who played this game through in 90 minutes flat with a group. He says that in each locale, they took the prompts as more or less one or two sentences. You move your coin to "standing by the river" and you say, my character stands by the river watching it go by. He has a quiet contemplative moment. Next!

We played this game for three years. As regular campaign where we would get together about every other week, I think in the end we might have hit 75 sessions , and we had to use Google Docs to keep track of all the characters we created. We, we spun up this gigantic world full of story together.

On average, people apparently play this game in maybe four or five sessions. So it's something that you're allowed to experience however you want, interpret however you want. It's an extremely open ended system, to the degree that it even is a system.

Mostly what it is, for people that are used to like solo journaling games,

It's kind of like a solo journaling game that you play with your

friends. It's just an open ended series of prompts to tell a story. And you can tell that story with whatever tone you want, with whatever nuance you want, with whatever level of detail you want, but at core, what it's about, which is kind of what we're here to talk about, is the map and how it tracks the journey that you take across the land.

Sam: Yeah. So, this game is mind blowing to me in its form factor, and the very idea of you playing this game for three and a half years is mind blowing to me in its... Duration in this way that like I so my experience playing this game. I went to a house con over the summer So it's just a weekend of playing games with one of my regular groups. And one of the days we dedicated to just playing Fall of Magic.

We spent about 12 hours. We did the whole thing start to finish we had to skip a few locations, but like all in all we had a pretty satisfying complete experience and it was really wonderful to spend so much consecutive time with a game. Which maybe makes my experience a little bit abnormal of it, but I think also around the median of how people play this game. But I had heard previously about the manner in which you had played this game, and I just could not... I'm sure everyone was sick of me by the end of the night bringing up like, how did someone play this game for three years? I don't, like, I have to know more. And so like, I, I'm so curious, before we move on to talking about the mechanic, to hear you talk in a little bit more detail about what in your play group's culture of playing this game allowed you to continue it for so long?

Tasha: I think part of it was just that we created a lot of ancillary characters. I think the way Fall of Magic is supposed to be played is you each have your signature character and your journey is the Magus and these You know, one to four individuals traveling with them, which by the way, I've also talked to a lot of Fall of Magic players or, you know, people who, I, I've talked to Ross Cowman about this a bunch, and he says that the Magus is also something that is very up for interpretation.

So for instance, he knows of games where the Magus was a seed that had to be taken to Umbra and planted. Or the Magus was a hat, literally a wearable item of clothing. Again, all of these things up to your own interpretation. So one of the things I did, just on a whim as we were starting the journey, was described a scene where the Magus said effectively that he had, he had like put a spell out there that would draw in anyone whose skills would be needed along the way.

And when he leaves that first location, I said, and there's about 50 people trailing along with him. And then I described, like, as we went to our second location and our third, how people would just fall off along the way. People who maybe liked the idea of the journey, but hadn't committed to it, didn't necessarily feel drawn.

But we still found ourselves in a space where... You know, for the first six months or so of play, we just kept inventing new characters. And every time we sat down together, somebody would be like, okay, here's somebody we haven't heard about before. Like, let's talk about the, clumsy, rich fellow that is constantly bragging about how he was the first to invent anything under the sun. And then somebody else would say, okay, and I'm playing his, kind of thick headed bodyguard who echoes everything he says and, backs him up. And then we'd just get into scenes with like, how do the characters we've already created interact with this arrogant blowhard and his loyal, trusty sidekick?

Sam: Yeah,

Tasha: But as the story went on and on and on, the two characters that I'm describing here deepened and became more complicated. Their relationships to each other became more complicated. They developed relationships with a lot of the other characters and they changed over time.

And change became a big theme of the game. You know, the relationships that all of these characters had with all of us picking up and putting down different characters in different scenes, it turned into Game of Thrones, except way less grim and with way less incest. As we just built this huge network of characters and then told stories about them.

Sam: Yeah.

It is remarkable to me, as you have mentioned several times now, how much room for interpretation there is in this game, both in the content of the fiction and in the manner in which you play it. And also how much consistency in terms of, like, tone and overall emotional experience I feel like I have observed in the people I have talked to about playing this game.

And find that fascinating, that by my estimation at least, the one beautiful artifact, and it's not just that it's a beautiful scroll in and of itself made with such wonderful materials, and those coins that feel so good in your hand. Like, the designs on the coins and the art on the map and the, the poetry of the prompts are all gorgeous in their own ways as well.

And all of that, like, collective aesthetic and poetry seems to do such a good job of setting, tone, and vibe that you, get a really consistent experience out of this game even though there's so many different ways to play it and so much up for interpretation .

Tasha: I mean, there's also just a self selection in the kinds of people that would choose to play this sort of game.

I have, at this point, I try to keep track of everything I play, mostly at conventions, some of them online. And I've played about 120 or so like small indie games.

And when some people say indie games, they mean things like Delta Green, that, that basically isn't published by Wizards of the Coast. But for a lot of us, indie games means something that was probably published by the developer on itch. io or DriveThruRPG something that was barely published at all. In many cases, something that went through a whole bunch of playtests at cons and was, was never published in any form. These just like really, really indie experiences.

A lot of them are about shared storytelling and shared world development. And in my experience that just draws a very specific type of role player, you know. A lot of the big mainstream games invite a bunch of different styles of play and draw a lot of different kinds of people. You know, you sit down with with three different D& D groups, you're going to see three very different experiences.

But in my experience, the indie RPG world tends to draw a very few specific types of people who tend to be very creative, who tend to kind of like live heavily in their own minds and bring their own entertainment, and who tend to be very collaborative and cooperative.

So, you know, if that's the kind of person that's sitting down to this game every time, that is going to flavor the kind of stories you're going to get.

Sam: Absolutely. I feel like there's a pull in both directions there of, kind of player you are describing creating a similar thing and the game kind of pushing them in that direction too. The game does feel, I mean, it does have such a, like, wistful quality to it, I feel like.

There, there is... I would stand By that the vibes of this game are extremely strong, and even if you're getting a similar kind of person coming to the game, like, the game is very clear about what it is, hoping you will push towards emotionally, I think.

Tasha: I mean, it's right there in the game. This is an autumnal game.

It's, the fall of magic contrasting with Ross's newer game, City of Winter, and games that he wants to put out in the future that are spring flavored and summer flavored respectively. This one is the one about magic dying, and I, I think that that also does color the kinds of stories that you're likely to be telling.

Sam: Totally.

Okay, so I want to talk a little bit about this game in the context of pair of episodes about travel that put out earlier in this season. So the first of those was about hexcrawls, which was great, and is sort of about the logistics of travel in RPGs. And I think logistical concerns can be a really interesting way to handle travel.

And then we also did this episode on Uncharted Worlds and Cramped Quarters, a PBTA move, in particular which is much more about the relationships and the emotions of traveling over a space and how you might build mechanics to see what happens to your characters during travel.

And I feel like Fall of Magic is really interested in the emotional experience of traveling, rather than the emotions that might spring up between travelers.

Like there's this feeling of grief as you were talking about, but also like nostalgia and reflection is a big part of what this game feels like to me, and, and it, it really feels so much like the calm, low stakes road trips across the country that I have taken. Like driving from Chicago to Los Angeles when I was making a big life change.

I feel like this is a game about capturing that experience more than the my character is getting mad at you for interesting reasons, like kind of experience that I talked about on this previous episode. How do you feel about what Fall of Magic is doing in terms of travel and emotions?

Tasha: I mean, I think your mileage is going to vary in terms of inner character conflict just based on how you want to play. Because I, I do play with a lot of people who really relish the emotions of role playing. And I think, people, in that mindset who sit down to this game are going to find a way to have those either player conflicts or player voyages of self discovery.

Because I would say Fall of Magic is also a game about discovery. You know, every new location that you get to is radically different from the last. And by choosing paths through the map, you're making choices about what kind of story you're going to tell, you know, are we taking a ship through something called the Salt Sea, which seems to be a salt desert, or are we taking a train? That is a very big setting choice as well as a narrative choice.

So there's a discovery factor there, but I think there's also just a sense of, this is a quest game. You have specific goal at the end and every step you take is getting you closer to the question of do we accomplish that goal or not? And if so, how, how do we accomplish it? Like ultimately, do we find what's wrong with magic and fix it? Or do we get there in time to watch the last bit of magic die out of the world or something else entirely?

So there's that sense of seeking closure, I think is a big part of this, this game.

Sam: Yeah. Yeah, I think another thing that you touched on in there is how much I feel like this game, more than other games with travel mechanics, is about place. That you're not, like in a game like For the Queen, a game that feels very much about travel to me, and that we talked about in that previous episode, not getting to a destination and moving on, you're between two destinations And maybe you're thinking about the space in between.

Whereas playing a full game of fall of magic, you're going to a dozen two dozen like interesting locations. There's almost like a tourist or sightseeing element to it that feels really absent from most other games about travel that I've played.

Tasha: But there's also a sense in each of those locations that whether what you find there is a matter for contemplation and for forwarding whatever internal story you're, kind of telling yourself, or whether it's a place of conflict.

You know, there were sites on the map that we treated as oases, you know, places for kind of like rest and recuperation and feeling our feelings. And then there were places where we invented in some cases very large, complicated conflicts that kept us in that location for months and months of playtime. So in each place, you're kind of Inviting the question within the story of are we tourists here or are we interlopers? Are we victims? Are we victimizers?

What does this particular location invite us to do or feel? And how does that affect our characters growth and our personal journeys?

Sam: Yeah. Okay, so before we started recording while we were kind of planning this episode you talked about, having two different ideas of what a map might be doing in a game at large. We're moving into talking about maps and RPGs at large. I'm saying it. Do you wanna like walk through what those two categories look like that you laid out?

Tasha: I think at this point I'm at three categories.

So we've got Fall of Magic and Ross's City of Winter and a very few other games that I've encountered. There's an as yet unpublished indie game that I've played a lot of at a local convention called Caravans, where you're traveling on a caravan. It's a long con game that's kind of designed for people to drop in and out. But the idea is that the story is centered around a caravan, and you collectively create a map as you're traveling, and then it becomes kind of a document of where you've been, where you're going, and as people come in and out of the game, they're invited to pick up journals that other people have left about the road and incorporate those ideas into their journeys as well.

So that's, the idea of a map as both kind of a document of travel and as a driver of travel. And that's the category I've, I see the least

Sam: Yeah, definitely.

Tasha: I never want to say in the indie game spheres, there's less of that because probably there's plenty of that and I just haven't seen it, you know, I think nobody can more than dip a toe into the sheer number of games out there.

I was actually, just before we started recording, looking at one of Itch's most recent game jams, which was the one page pen and paper RPG. 600 plus entries. And I looked at a few of them around maps and found some really interesting stuff, but like, who has time to even read 600 RPGs, even if they are all one page long?

So I won't say that there's less of it, but I've certainly seen a lot less of it than of the other two types.

The other two types that I've seen most are artifact maps, which I've seen a lot of them in, I'm currently in a Dungeons and Dragons game, 5e, based in the Wild Beyond the Witchlight setting. And if you purchase all the ancillary stuff for that campaign, it comes with a ton of maps. And those maps have no purpose, really, other than laying out where everything is in position to everything else, just kind of giving you a visualization.

There are a lot of games like that where I think, Stone Top comes to mind as an indie RPG where you start with a big map and then you kind of decide collectively your community's relationship to different things on the map. But it's a set map to begin with. That kind of like map presentation is basically, here's a setting. What are you going to do within it? Like, what kind of choices are you going to make? We're not going anywhere. It's not about travel. So the visualizer map I guess would be the second category.

But what I see mostly in the indie sphere like more than anything else is collaborative map building as a way of world building. And with this I'm talking about games like The Quiet Year or Companions Tale or i'm sorry did you say street magic? These are all games where you sit down with a blank sheet and you start creating a world together. And you often alternate putting things on the map or defining things.

One of my favorite indie games these days is, have you ever played Nick Wedig's Rusalka?

Sam: No, I saw it being offered at Games on Demand several years ago, and was like, I gotta play that, and it just, it was one of those ones that slipped by me.

Tasha: it's fabulous. I love it. I have played it multiple times with Nick, and I've taken it to other cons and run it. I've run it for friends.

It's a card based game just a series of decks of cards, and the theme is that everyone is both a Rusalka, which is to say, a Russian ghost of a drowned woman Given strange and specific powers or a petitioner to the Rusalka, somebody who's come to the pool where they drowned to ask a boon of them.

And you trade around the table with your card decks picking up petitioner cards and playing out the sequence where you come to the pool and ask the Rusalka for your favor and they decide whether to grant it to you or not based on the cards in their hands. And then you all play that out.

But the way the game begins is you all collectively design a map of the pool, and as the game proceeds through various ages, you make changes to that map over time to show how the area has changed, how the community has changed, how far in time you're moving forward, and what kind of things have happened.

So, there's a storytelling element to the collective map building game that I really like. It's just all about, again, using the map as a visualizer, but also using it to develop your story and develop your setting together by adding or subtracting or changing things on a map that you all share as a story element.

Sam: I think that this is something that's especially true of those, like, create a map collectively games, but it's kind of true of all maps, is that when you put a map on the table in the center of everyone, It brings everyone together around this shared object in a way that is really wonderful to watch. It really invests everyone in this centerpiece of play.

And especially when you're creating that map yourself, it becomes this object that, like, lives in the fictional world and the real world. It feels like a portal between the two, almost, especially as you are adding to it and drawing on it.

And I remember back to like my first experience playing Dungeons and Dragons with my dad who introduced me when I was in like the third grade and him like come into the first session with a like color pencil drawing of a continent on loose leaf paper and losing my mind at how cool And I feel like you still get that experience when someone pulls a, Dungeons and Dragons map out of the D& D book, like, like whatever you're doing, putting the thing on the center of the table, it, it really, people put down their phones, you know? People focus on the thing. And I, think maps are really wonderful for that reason.

Tasha: Yeah, there's a lot of, I think, play in the indie space that's built around making artifacts of some kind. The Slow Knife is a game where you create string board, a conspiracy board of connections together. At Origins this year, I got to play a Liz Stong game that I thought was really cool called Drawing Out the Demon, where you all collectively draw art of animals. And then there's a series of rounds where you're creating animal art, and your artists are like trading feedback with each other.

Sam: Hmm.

Tasha: And then you skip forward, have you done

Sam: No, I read it because it's a Golden Cobra game. It's one of the Golden Cobra games that I've read repeatedly because I just get a kick out of it every time I read the rules. I've been trying to play it for years. I really love

Tasha: It's amazing. It's an absolute hoot. Yeah, she ran it at Origins. So you, you create this art, this very bad art of animals, and then you skip forward to the modern day and play art critics explaining things about the artists based on this terrible art, and it's all about misinterpretation. It's all about the loss of information across generations. It's all about the pretentiousness of uh, of art critics. It's hilarious and a lot of fun.

But in all of these cases, these games are about collectively creating something physical that sits in the space between you and unites you. And I feel like the map making game is kind of the purest form of that.

Sam: Totally. Yeah, there's something about all collaborating on the same artifact I think the creating an artifact when I play, brings me into the fiction more, but creating the artifact with everyone else at the table also brings me into the fiction, like, together, instead of just sort of by myself into my own little artist's head, you know what I mean?

Tasha: Yeah, and then you're not only creating a shared artifact, you're creating a shared artifact that not only are you occupying, but that you know as you create it, it's meant for you to occupy. So when you're playing something like The Quiet Year, there isn't just impulse to, the same thing goes for Rusalka for that matter, maybe for a lot of these games, you're not just saying like, okay, there are a bunch of mountains over here, you're incentivized to say, There's a dark forbidden pool over here. There's something lurking in the bushes around it that is never seen but only heard.

And now you've created part of a story, you know? You've created something that you or someone else in the game is going to interact with. You're creating the space that you want to play in. Which, you know, when we're kids, we build pillow forts. When we're adults, we play indie role playing games and create maps, but it's the exact same impulse. You're creating a world for you to play in, and you're creating a space for your characters to occupy.

Sam: Yeah. So, I want to go back to the kind of map that comes in like a D& D book and the Wild Beyond the Witchlight maps that you were talking about. Can you describe those in more detail? Like, what do those things look like?

Tasha: So, the gist of that story, that setting as I understand it is you start at a carnival and you end up in the Feywild, and you have to travel from land to land in the Feywild. So, the first map that we saw was just the carnival, and literally just kind of physically laid out. All of the different rides that you could take or games of chance you could play, or, here's the hall of mirrors and here's the hall of illusions.

As soon as it was on the table, we were all like exactly like little kids at the carnival. We were all shouting, I want to go to the snail races. I want to go ride in the bubbles. Like we could all see that there were things on the map that we were going to be excited about and that we wanted to go do right away.

When we got to the Feywild, and we're looking at these you know, here's the local land, it feels a lot more like it's just about, well, for one thing, those maps aren't labeled nearly as much. there's a series of numbers that, like, over here is number four, and you have to go to number four to see what it is. It's not like the Carnival map. where you might see a carnival map, like, literally on a board as you're coming in, telling you where everything is.

So we found ourselves, because of the existence of the map, probably exploring a lot more of that map than we would have otherwise. We came to the first land that we visited in the Feywild with a specific agenda and a specific person to visit. But because we had the map in front of us that said, you know, there's something over here. You don't know what it is, but there's something over You gotta go find out what that thing is! Like, it's gotta be interesting, right? It's all, it's literally on the map.

Sam: Yeah. okay, so the, when I picture a map coming out of a D& D book, I picture my college 4th edition Dungeons and Dragons Dark Sun campaign. And the Dark Sun campaign setting came with this, like, continent sized map that folded out to be, you know, like, four feet by five feet or something and had a scale of miles and Nine different important cities on it and a bunch of other stuff like secrets about the world embedded in this map.

And I remember... I remember that kind of map providing this sense of scale that the world was so big. That this campaign setting was gonna contain everything we could possibly ever want because the map was so big. And I I think that the feeling of the world is so much bigger than you is if that's a feeling you want in your game if that's a feeling you want In your experience, like, a big map was a great way at instilling it in me.

Tasha: yeah, as it happens, I was also in a different D& D game that ran for about three years that kind of sustained us during quarantine, during the pandemic that was set in the Forgotten Realms./ And the game itself was kind of built around a giant published map of Faerun.

Faerun? I don't know how that's pronounced. It's a word on a map to me as opposed to a pronounceable

Sam: with too many, like, umlauts on it, too.

Tasha: So many umlauts.

And, you know, the, the Sword Coast map, I've just pulled it up on my computer while I'm sitting here, gives you exactly that sense. This is a huge epic scale thing. You can go up into the mountains, you can go off into the islands, you can go down to a completely different continent. And we did, you know, we ended up traveling to different continents.

When you can see how far everything is apart it gives you that kind of, that sense of like, this is an epic world. There's something that just doesn't feel complete about a GM telling you, Okay, so you travel for 16 days and then you get there. And, it's, it's just, it's not the same

Sam: What happened to those 16 days? Like, I don't know!

Tasha: Eh, not much. It was actually very boring. You were very bored. Okay, fine, you've had 12 random encounters, let's play through all of them, if you insist.

One of the things that I'm seeing a little more of that kind of fascinates me is people, you know, there's a whole sphere, particularly for Dungeons and Dragons, of people creating ancillary adventures and selling them under license. Now we're seeing more and more people creating artifacts, like maps.

One of the things when I was just kind of like nosing around to see what all exists in the you know, in the map sphere that's interesting in kind of bigger RPGs was a book called Doskvol Street Maps, detailed maps for Blades in the Dark. You can get that on drivethroughrpg. com, and it's basically just a bunch of like, big sprawling hyper detailed city maps for a primary Blades in the Dark setting.

Sam: I should mention that Tim Denae listens to the podcast, Hello Tim, your maps are great.

Tasha: Oh, hello! So, you know, this is something where people who are, like, as their side hustle, developing their creativity into a saleable thing, you know? I have built this huge world I can help you play in it. You know, I have built this complicated setting. I have created this really rich artifact. Why not sell it to other people who will find it very useful?

Sam: Yeah.

Tasha: And things like D& D maps or, you know, these Blades in the Dark maps or whatever game you can find, like, support maps for, it's both a way for... You know, Wizards of the Coast can turn out maps all day and just, they're constantly trying to figure out how to, make this a viable business, you know? How to how to sell something new to the same gamers without just making it look like we've got another edition of the game. Now you've got to buy all the rule books again.

So, you know, big, elaborate, beautiful maps is something that appeals to a lot of people in the gaming space. People who create hyper detailed things like these maps of, of Doskvol, why not share them with other people? And why not find a way to, you know, monetize a skill that you have at creating something really neat?

Sam: Yeah. I mentioned earlier this idea that I was looking at this, like, Dark Sun map and thinking, wow, I never need to leave this campaign setting because there's so much here. And that's another reason I think that Wizards is so excited to include maps in its publications, right? When the map is big enough, you don't need to ever leave to try something else out, and, for that matter, you don't, Why would you leave before you've explored the whole map? There's so much more to do here.

And as much as I love Tim's maps and think that they're beautiful and you know, like that, that thing is out there, I have friends who really have relied on those maps while running Blades in the Dark campaigns.

I also sometimes feel like the maps get so granular that they stop leaving room for invention at the table and stop leaving holes for you to fill in with whatever story it is that you want to tell.

Tasha: Again, it depends so much on the type story you're, telling. If you're playing a Blades in the Dark game where it absolutely matters, you know, the heist is here, you have to escape to here., Here's what's in between you and, and there. It's like playing a d d game on a, a hex if you can abstract an awful lot of D&D combat or you can do it all with minis on a board where the positioning matters and the system is, I think, more made for that. But you, can do it either way.

Sam: Yeah.

Tasha: I would prefer to play Blades in the Dark as a more of an abstraction in terms of like where you are and what you're doing and make it a little more about story, but especially for like heist or crime related stories, I can definitely see where having this level of detail and understanding where everything is in relationship everything else could be crucial for a specific kind of game.

Sam: Yeah, totally. Totally. The other thing that Tim Dene has put out is this Blades in 68 project, where you basically rolled the whole timeline forward a century on Blades in the Dark, so you end up with this, like, 60s or 70s feel and technology level, rather than a, like, 1800s steampunk era. And, he's basically been releasing the whole thing just in a Twitter thread which I think has moved to Blue Sky now, I'll link it.

But the first post is just an updated map. It's just a new map, and instead of electric lightning barriers around Dustbowl, now there's a big bubble. Oh, and it's daytime, too. And just like those couple of like setting changes that are observable just on the map of a place really do this amazing job of completely resetting the tone of what this game was originally.

I think that's true of maps like across the board, like every single map we've talked about today, whether it's Fall of Magic or the map that people are creating themselves when they're playing The Quiet Year, or whether it's a big D& D map, does such a, such a good job of setting the tone for whatever it is that you're doing next.

Tasha: Yeah, it's what I love, the collaborative map specifically in Quiet Year or Rusalka or any of these related games. What I love about it is that sense of change over time, you know, a lot of these games have specific either mechanics or prompts just to change things on the map.

You know, I, remember a game of Rusalka where two of the things drawn on the map in the first phase were like a vast alligator that lived in the depths of the pond, there was just this predatory monstrosity, and an old temple at the side of the pond. And as we moved forward in time, the temple crumbled and became a ruin, and the monstrosity died, and then something new and horrible was born from its bones. That, that sense of, like, invitation to create a change in an environment that you've already .I think it's just really illustrative of, of time passing, things moving forward.

Sam: Well, it's, it's so cool, too, how just changing one image on a map, like a symbolic image of a tower from constructed to ruined, conveys so much so concisely. And no, that's the end of my thought.

Tasha: Well, the same thing with, with adding something, you know, adding bubble around the city in Blades in the Dark, it's just, you showed me that map, I had never heard of this this new iteration and it kind of gave me the shivers. change from this, like, sort of weird, ancient, like, neotech sense to this kind of oppressive future tech just just within the, the course of like drawing what's essentially just a barrier around a city.

Sam: yeah, and he released, like, a preview image before that big main map even came out, and just the preview image was like, that's Doskvol, but it's daytime. What's going on here? Like, it was so intriguing just by changing the one little thing.

So, coming off that idea that, like, one detail on a map can change so much, I think something that is super impressive about Fall of Magic is just how little there is to the game beyond the map. You can go back and listen to an episode I recorded with Jason Morningstar where he kind of disagrees with me about this.

But there's... There's just this map in front of you, it has these prompts, it creates this ritual of play of going around the circle and framing scenes, but it is also... Most of these prompts are really a image of a location and like three words and you're able to get, you know, three years of campaign out of that little. I, I'm I'm curious to hear why you think that works.

Tasha: I feel like what makes Fall of Magic such a cool game is the fact that the central artifact, the scroll, is so unique among games. Like, I said earlier, there are a billion indie games, nobody has investigated them all. And anything that you think, well, there's... There's none of this in the indie sphere, there probably is and you just haven't encountered it. But I feel pretty confident in saying that this like physical, handmade, screen printed canvas scroll is a pretty unique artifact among indie RPGs.

So the fact that it's so central, it's so tactile, it's so much the driver of the story, I think is, is just like a focus item in a way that lot of the maps we're talking about are, but maybe more so just because it's, you know, just such a, a unique and detailed thing. I think it's very uniting to make your own map together, but there's something, I guess, to my mind that's special in a very different way about having this, like, beautiful piece of created artwork sitting in front of you.

Sam: That reminds me of... Again, being in the third grade, playing Dungeons and Dragons for the first time, and the tactile obsession with the dice set that my dad had gotten me. And of course, a dice set, you know, there's as much there as there is. You're gonna use dice for a long time, they're a very, like versatile sort of object, but you, you lose some of the, the luster of like, what are these weird little, occult stones that I have been gifted and that feeling, I think you're right that like, the, the map of Fall of Magic captures that feeling of just wanting to play with the physical thing in a lot of ways.

Tasha: Oh boy, that said, the ritualism around dice in just the gaming sphere at large, I don't know that a lot of people have lost that sensation of being a kid that wants

to play with the magic stones.

Sam: that's true, yeah, I I know plenty of people who have built physical dice jails, so yeah, mean, maybe, you're right. You're absolutely right.

Tasha: Yeah. And just like the, the degree to which people like love their newest set of dice, their fanciest set of their most creative and unusual set of dice. Like there is a, a love of the unique and specific, I think, in the gaming sphere that extends both to like, look at my new shinies, which is a phrase I have heard many times around people's dice. And, you know, look at this beautiful physical thing that we're all sitting around and using as a focuser.

Sam: there's something like my partner is a theater director and I am a filmmaker TV person and we talk a lot about liveness in my household and the value of liveness, how that is the thing that theater can bring to storytelling that film is never going to exactly. And think roleplaying games also have that quality to them, that one of the beauties of the medium is that you are all there in person, and having the artifact that makes use of that feeling magical.

Tasha: Yeah, we're just getting to the point where you know, our, groups are trying to meet in person regularly again, has become difficult because during quarantine, we started playing more and more with people in different cities, you know, friends of ours that have moved In some cases to different countries.

And so playing a game like Epidiah Ravachol's Dread, it's my favorite horror game, and which is built around a Jenga tower. Like playing a game like that, that relies on a physical item, has become difficult to impossible. Playing for queen, which relies on a set of cards, like you've, you've got to have a digital version of it.

But maps for the most part are something, pretty much all of the games that I know that use maps, they're digital versions of them, and you can still use them as the center of play. There's a digital version Fall of Magic for online play. And you know, PDFs or other image based artifacts for a lot of these games that sell their maps. And if you're making your own map, there are ways to, create that digitally.

So a lot of, like, the magic of in person play can get lost when you're playing remotely, but at least there are still ways for you to all gather around a map.

Sam: Yeah, it's true. You know, we were talking about dice there, and Fall of Magic, at least in its travel mechanics, doesn't have any dice, and I think of the other, like, big travel games that I think of are PBTA games with travel moves, or with something like For the Queen, where you have the, you're drawing cards from a deck, and there's still that element of, like, randomness to the travel. And Fall of Magic It has very little randomness to it, and I think that changes the way travel feels.

Like, you're never thinking about random encounters, you're much more lounging, it feels like, or like, living in feeling of the moment more. I'm curious if your experience matches that or not, or what you think randomness would bring or take away from travel in this game.

Tasha: Well, here's where I fess up to the fact that we periodically would introduce randomness into of scenarios we're playing in Fall of Magic.

Sam: Yeah! Well, what did that add?

Tasha: Well, I mean, it adds, it adds a sense of stakes, I think, but it there is a problem, like I've played story based games with strangers at conventions. And once in a while, you will come up against the problem of, you know, we have created characters that are at odds with each other. I want to win this fight. You want to win this fight. Most indie games that allow that kind of thing will have some sort of, you know, well, agree among yourselves who wins and why and and how it goes. And that can be much harder with strangers.

So having a simple mechanical resolution, I think, can be a good thing. But sometimes you just don't want to sit there and decide among yourselves, like, here's a massively important point in the story. Are we just going to tell each other, and this is how the story ends? Or are we going to, like, let chance take a hold in it?

So there were a number of times over the course of our Fall of Magic game where we said like, let's let the dice decide who wins this fight or who gets this magical artifact. Is that a good or a bad thing?

I don't need crunchy games at all, and I don't get the kind of like glee of getting to roll like a big handful of a lot of my friends get out of games like Champions or Exalted or whatnot. It's just not an inherent thrill for me to say, all right, I'm rolling 24 dice right now.

Sam: Yeah.

Tasha: But I do like having that element of randomness where you don't know what's going to happen, because it feels like a risk.

Sam: Yeah. Yeah. Totally. I should do a whole episode on fortune rolls and Blades in the Dark and that exact dynamic.

There's something else in there about the feeling of playing with strangers and allowing the dice to be sort of a mediator between you in terms of how to resolve something that makes me think about do you think it's too light a game for some people? Like the person you described playing it in 90 minutes at the beginning of this episode, like, they're almost done now. You know, they're, they're coming up on the end

Tasha: hey, hey, I

Sam: their, entire campaign of this thing is like, did they enjoy the, that experience or, or did it feel too slight to them?

Tasha: He, when he was describing that game, he certainly sounded like he didn't much care for it. Like his group didn't find a whole lot of presence there or tactility to it. It sounded like he would have been much happier playing, he... You know, 40k or something like that, something lot more mechanical. But that's fine, you know, everybody has different tastes. It's different squids for different kids, as Robin Hitchcock used to say. Takes a lot of takes a lot of different kinds to make up a world, and that's fine.

But yeah, absolutely, this is too light for some people you know, if the idea of like, sit down and make a campfire story together sounds appealing as opposed to dreadful, this is the kind of game that you might like. If you've enjoyed For the Queen, this is the kind of game you might like. But I'm sure that For the Queen is also too rules light for some people.

Like,

Sam: I gave it to my parents and they could not make any sense of it.

Tasha: if you decide you want to kill the queen and somebody else doesn't, like, how, how many dice do you each roll?

Sam: Yeah.

Tasha: does your armor play into effect? What about the

Sam: Well, you get one die for every question you've answered correctly throughout the game. Yeah.

Tasha: which you yourself have to determine, as opposed to how many you just completely lied about?

Sam: Yeah. Okay, so I want to get us to City of Winter because I think City of Winter also is, I know very little about City of Winter beyond the basic elevator pitch but I know that it adds substantially more mechanical complexity. So I'd love to hear you just tell me a little bit about how it changes from Fall of Magic and, and what you think that does to the basic game. Because it's still got a big, long scroll as its, defining feature, right?

Tasha: It has a big, long scroll, and then there's a second piece, which is a city map, because the idea you're traveling to a city, and eventually, hopefully, you get there, and then your story continues within that city. That piece that I wrote for Polygon people looking for it can find it under the headline, "Why hang a game map on the wall when you can build a world around one instead?"

Sam: or you can find it in the show notes.

Tasha: oh, there you go. that piece was specifically written about the Kickstarter for City of Winter. And Ross talks a bunch in that article about the decision to make a scroll on a map as opposed to two scrolls, or a scroll with unfolding panels to make a city, or some other mechanical idea. There were a lot of considerations that went into how this this game is, like, physically structured around maps.

But I think the big difference isn't in the mechanics, which does involve dice occasionally, and cards, and keeping track of a whole lot of stuff, and creating artifacts. I think it's less in that and more in the theme of the game Fall of Magic.

As I said, I think Fall of Magic is a very autumnal game, it's about the dying of magic in the world, and like, that slow slide towards a conceptual winter. City of Winter is expressly about generational change and loss. The idea there is, once again, you're playing characters on a journey, you have to leave your home because the Umbra is coming. The Umbra is an undefined thing that you have to create for yourself. What it is and what it means is just all part of the story narrative. But you create characters who mechanically age over time as you move from locale to locale. And some of them will eventually die, and then you'll create new characters.

You're meant to play collectively a family, like, from generation to generation. And kind of of the game is about the traditions that you bring with you from your homeland, how you lose those or they change over time, what kind of traditions you pick up from the communities you pass through along the way.

And what's lost as, as people age and die. And thematically to me, it feels a lot darker, which I guess

Sam: Yeah.

Tasha: a winter game. But a lot of the mechanics that that game has that Fall of Magic doesn't are in part meant to enforce the idea of generational change and letting your characters go.

One of the things that Ross talked about a bunch when we spoke was just people invest themselves so much in their RP characters and they don't necessarily want to play their deaths out and then move on to the next one.

You have to have like a specifically designed system to invite them to do that and they have to know at the beginning of the game that this is part of the story, is how things are going to change when you're, you know, your teenager becomes an adult, becomes an elder of the clan, and then passes on. And then what does the next child born into that clan know about that elder? Like, what did they successfully pass on that's still in the family? And what was let go over time?

it's a very neat and very heady concept, and it's all built around the same map. Well, not the same map, but it's all built around a similarly conceptualized and constructed prompt based map.

Sam: Well, and of course, Building space for people to feel comfortable giving up the character they've invested into is presumably important in a game that is going to require doing that a lot of times, but it seems clear that the game is also about that feeling, that it is about that moment of giving up your character and having to say goodbye.

There's something, when we were talking about map making games earlier, like The Quiet Year and Street Magic, that I wanted to mention where those games operate very much on like a bird's eye community level for the game. And I think the map allows you to come up to that bird's eye level like above any one character. You know even if you're gonna get down into the weeds with certain characters at certain points and feel emotions from them, that you're going to then return to your perches looking over the map.

And in some ways, I feel like what you're describing in City of Winter feels like it's weaponizing that against people's feelings, that like, like, you're, you, you're gonna have to go back to that position even though you don't want to, and, and what is that emotional experience like?

Tasha: I think it's also worth mentioning, given the conversation we were just having, that the point where your aged out character dies is determined by a dice roll.

It's a, dice roll that becomes more and more likely over time. But I, I ran this game for strangers at a Games on Demand session at Origins. And one person at the table, you know, her elder was coming up to the first round in which she could die. And I said, you know, we're nearing the end of four hour slot, like, you probably don't necessarily want to start a new character right now. Do you want to forego this roll? And she, she kind of poo pooed it. She's like, I've got a one in six chance. What's the worst that could happen? There's, there's no, of she rolled the one.

Sam: Yeah, I'll tell you what the worst is that could happen, yeah.

Tasha: So once again, the dice contribute to decisions being made that would be uncomfortable to make for yourself, the of you and I go sword to sword, which of us wins based on our kind of internal ideas of who our characters are and who we want to be can be very difficult and rolling dice helps with that. Letting go of the character that you've invested in emotionally can be difficult and the dice help with that by kind of telling you, when it's time.

And I think also just really adding to the sense of none of us know when we're going to die, you know, we all hope that we'll like live to be 110 and still hale and hearty and playing role playing games every weekend. But we could all get hit by buses tomorrow collectively. Like the same bus at the same time. Really unlikely, but you know, sometimes you roll a one.

So, adding that dice mechanic to City of Winter, I think, kind of takes you off the map, literally, and into a place where you don't entirely know the future.

Sam: Yeah. I cannot wait to play City of Winter. Do you have anything else you want to mention about it?

Tasha: I haven't, obviously, after three and a half years of Fall of Magic, and like, only a few months of playing City of Winter with the same group, I don't know that I've dug into it enough. I think thematically, City of Winter just, may never have my heart in the way Fall of Magic does because I'm never going to be able to have that first experience with those three people in the same way again. In the same way, you're never going to watch a movie that makes you feel like, I don't know, maybe Star Wars made you feel when you were seven years old. That probably just isn't gonna happen for you again. And you have to embrace what it's like to see a really cool movie in your 30s or 40s and how it's just a different experience.

Sam: Sounds like you're embracing the themes of City of Winter.

Tasha: I'm, Lord, I'm trying to, except for the where I have to roll a die every day to see if I, if I keel

Sam: Mm.

Tasha: I feel like I haven't dug into it enough. Running it for strangers and seeing how it played as a four hour, like, time limited game was very helpful for me in terms of, better understanding how it's supposed to play for, you know, more, ugh, words like regular or ordinary just sound so dismissive. How it's supposed to play on average, as opposed to how my weirdo group plays it.

I like it a lot. I think it's very smart. I think it's very dark and sad. You know, I've, I've played Ten Candles. It doesn't help know at the beginning of the game that your characters are all gonna die. You still get sad when it happens. It's still kind of shattering.

And same thing with City of Winter. It's a difficult thing to happen, but we're only halfway across the map, and we haven't even gotten to the city yet, so I feel like there's still a lot of that game to, you know, coming back to the map concept, there's a lot left to explore.

Sam: Yeah.

Well I feel like we've certainly covered one location's worth of exploring this omnibus, uh, edition of Dice Exploder. Uh, is there any, any final one of words you want to leave us on?

Tasha: I have 28 more topics to introduce, and then we're going to talk each of them relates to each other, and we're going to stay in this location for like twelve more podcasts.

Sam: I mean, honestly, if you want to come back 12 times, like, I can arrange it.

Tasha: podcasts. Or we just move on to the next location. Maybe roll a die to

Sam: yeah, yeah, yeah. I'm making the call. I'm making the call. Tasha, thank you so much for being here.

Tasha: This was delightful. It's just, it's, I know I tend to hold forth. I have a lot of opinions about a lot things. But man, it's nice to synthesize. A lot of these games that I've played into, what are the ideas here? And just, like, really get to think about that in a way that you don't think about it when you're sitting at the table being somebody else and trying to invest in that experience.

So this was a lot of fun. Thank you for having me.

Sam: The show is over, but if you want more, you can go donate to the Season 3 Kickstarter for Dice Exploder right now to immediately get a sweet bonus episode about EXPLODING DICE featuring Mikey Hamm, designer of Slug Blaster. Don't miss out.

Thanks again to Tasha for being here. You can find her on socials at Tasha Robinson, or her current writing on Polygon, and of course, the Next Picture Show podcast, of which she is a co host, wherever you get your podcasts.

As always, you can find me on socials at sdunnewold, Blue Sky, and Itch Preferred.

And there's the Dice Exploder Discord! Come on by and talk about the show. We got a lot of new folks this week, and it's become a real bustling place. I'm just so pleased with the thing that server has become.

Our logo was designed by, I've been told, I've been saying this wrong, Sporgory? Hopefully that's right. And our theme song is Sunset Bridge by Purely Grey. And thanks, as always to you, for listening. See you next time.

Share this post